On any given day, the center run by the Commission of Women Victims for Victims (KOFAVIV) serves as a sanctuary for the brave hearts of Haiti’s rape survivors.

I first arrived at the KOFAVIV Center in 2011, more than one year after the earthquake. A timid breeze entered the courtyard shaded by three almond trees. A couple dozen women sat in groups of four or five, talking amongst themselves. Even though some were outspoken and others were more reserved, probably new to the Center and their activities, they all smiled and laughed together. After a few minutes, the small groups formed one big circle and started to vehemently clap and chant an ode to their strength and dignity, one that I would hear repeatedly over the following years, coming from the diaphragms of impoverished slum dwellers and disenfranchised peasants across the country.

‘Nou se wozo.. nou pliye nou pa kase’ (We are like a reed… we bend but we don’t break)

It was evident to me that the force behind the chant was not gratuitous. The analogy of people embodying the flexible strength of a reed reflected the stoic tenacity for survival with which one’s mind reacts to extreme suffering. Academics call this resilience.

KOFAVIV was formed in 2004 by a group of rape survivors, in order to support thousands of other women that, like them, had been victimized during the country’s perennial epochs of political instability. The organization housed a small clinic to treat women who had contracted HIV and other diseases as a result of rape. Just a few days after the earthquake hit Port-au-Prince and destroyed the clinic, the group began helping the new wave of rape survivors out of their tents on Champ de Mars square, across the street from Haiti’s crumbled presidential palace. In the years that followed, these women have not only provided free medical, legal, and psychosocial support to hundreds of rape survivors, but it has trained them to become community leaders and ‘field agents’, identifying and addressing new cases of rape in a large number of camps and impoverished neighborhoods in Port-au-Prince.

Although the exact number of women and children who were raped in the aftermath of the earthquake is impossible to know, studies estimate that a staggering 22 percent of displaced persons and two percent of the general community were victims of sexual assault.

I asked one of KOFAVIV’s staff how old was the youngest victim in the center that day. She responded that there was a 2 year-old girl being cared for in a private room.

Since that day, I have followed, supported, and observed KOFAVIV’s tireless work. I chose to do so not as a journalist, but as human being. By sitting in their discussion groups and community meetings, I initially hoped to find an explanation to the wave of sexual violence affecting the women and children living in tattered tent encampments. However, it didn’t take me long to realize that I was wrong to try to rationalize the violence, and that I was in a privileged position to learn from the fortitude and dignity of each and every woman at KOFAVIV.

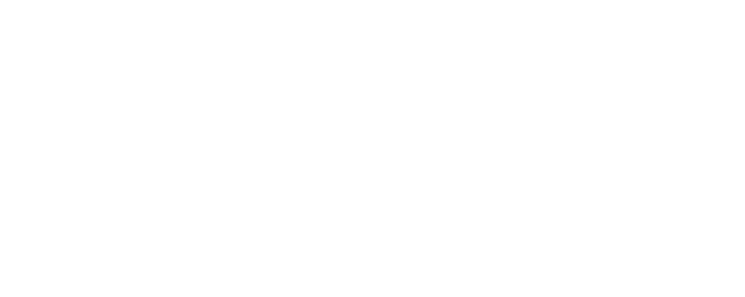

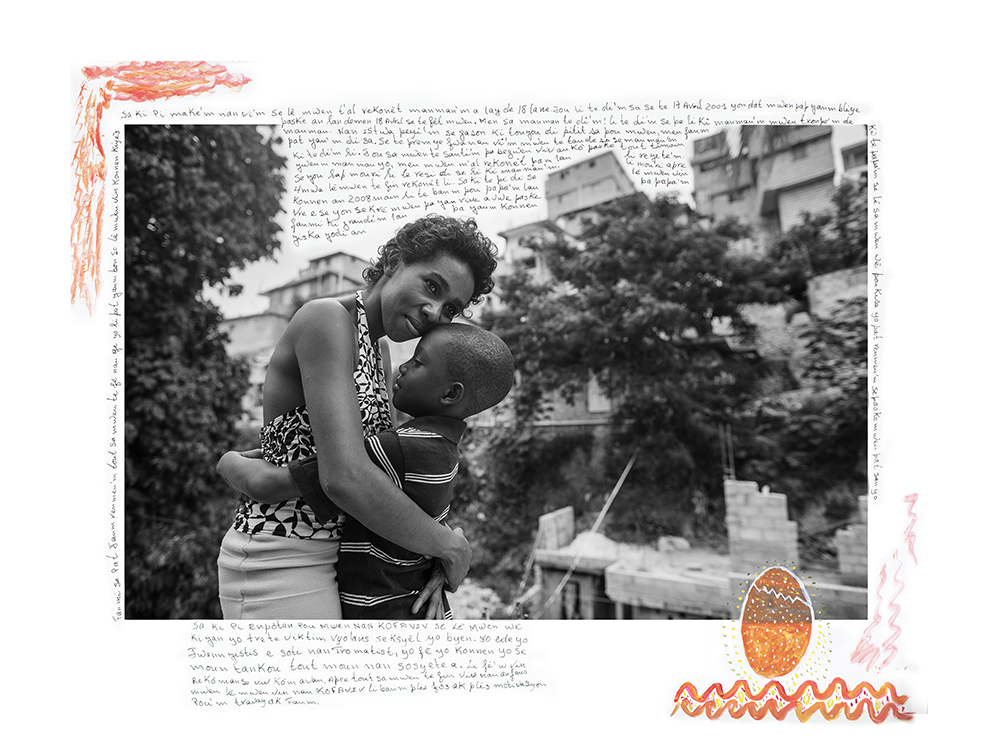

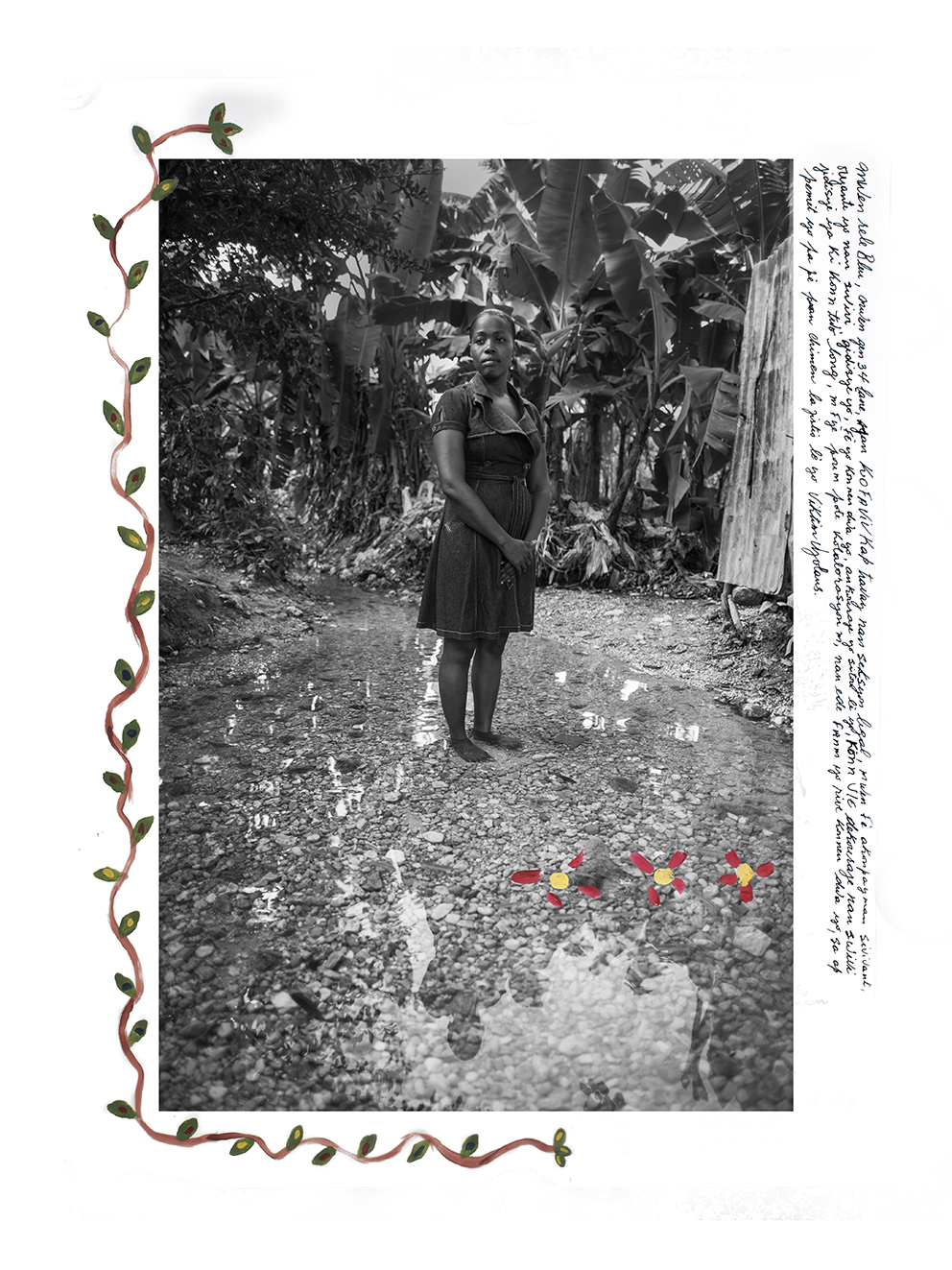

In March of 2013 in one of my visits to the Center I learned that most international funding for KOFAVIV’s activities had ran out, and that the organization was scraping by to continue to support the rape survivors that arrived at the Center. In a conversation with KOFAVIV’s leadership, I proposed to implement a series of workshops to document the work of twenty of their members who had been at the forefront of the struggle against sexual violence for the past few years. Keeping in mind the International Guidelines on Reporting Violence Against Women, we sought to include these women in the creation of a collection of visual testimonies that avoids falling into the simplistic re-victimization of rape survivors by depicting them as strong, dignified, and active members of society.

For nearly 6 weeks, the women participated in a number of writing, painting and photography workshops that allowed them to tell their personal stories and take stock of their work helping other rape survivors. The final result of the workshops combines the written testimonies and artistic expressions of these women with a portrait of them taken by me. We sincerely hope that these images serve not only as a small window into the women’s stories of violence, but on their life experiences, on their vision of the state of women in Haitian society, on their hopes and fears, on their frustrations and their dreams, and on their stoic tenacity for survival that has never ceased to amaze me.

– Felipe Jacome

“‘Nou se wozo.. nou pliye nou pa kase’ (We are like a reed… we bend but we don’t break)”